This article is in response to the questions I get about ‘what should we do about toxic masculinity influencers’. I complexify the idea of an individual having a singular ‘effect’. I argue that there are potential harms of uncritically accepting a common sense ‘cause and effect’ discourse of toxic masculinity. How paying attention to those discourses ‘covers over’ failings which are closer to home. Lastly, how the solution has been there all along, but it’s our own embedded institutional toxic masculinities which prevent us from accessing them.

Andrew Tate and other toxic masculinity influencers cause a lot of harm. In person (as we are seeing) and also via the messages they articulate. Their hateful, misinformed, sexist, and violent discourses (stories) are harmful. If they are repeated, in school, in RSE, in exercise books, in corridors, in the playground etc this is also harmful. It’s also hard to deal with, because often it’s harming our students, or us, or our loved ones. But we have to address this topic with the complexity it deserves.

(If you don’t know about Andrew Tate, here’s a useful podcast from Sky News)

‘Entanglements’ not ‘Effects’

I think we have to be careful when we talk about the influence that people have on people, or the effect that celebrities, influencers, or media have on people. Toxic masculinity influencers aren’t making young men think in a particular way. Influencers, celebrities, and media don’t cause ‘effects’ on us in this way, it’s much more complicated.

There’s a huge amount of work on critiquing ‘media effects’ models. We’ve known for many years that young people, even children from an early age, are able to bring a high degree of critique and media literacy to media.

We bring with us our own values, experiences, understandings and bodies whenever we encounter celebrity discourse, influence, media, or porn. So rather than being passive sponges soaking up ‘an effect’ and unconsciously reproducing an ‘influence’ we encounter these discourses in a complex entanglement.

So, for example, a young man who is a fan of [insert toxic masculinity influencer here] is an entanglement. This might include the following relationships:

school — phone — dad — height — clothing — own experiences of violence — anger — dating — fear — where they live — muscles — puberty — penis size anxiety — football — their pet — RSE — tiktok — dad — queerness and feminism as ‘Other’ — online spaces — their future — disconnection — the word ‘gay’ — history — unrequited enamorations — shyness

Here’s a really interesting article about young men’s entanglements / assemblages.

Why is this important?

It might sound like I’m nitpicking. I think it’s important to be more precise about how we talk about the ‘effect’ of toxic masculinity influencers. This is because:

The influence isn’t the outcome

Any influence of misogyny is reproduced by young men because they, in some way, want to. It’s important not to lose the intentionality of this because this lets men off the hook. Just like the argument about video nasties, violent video games, rap/grime/drill, or pornography making someone more violent. We don’t accept this argument for these forms of media and we shouldn’t accept this for influencers either. It’s inaccurate and leads to bad outcomes. Their motivations for doing it might be very different, but that’s something else I’ll come onto later.

There isn’t just once influence

There are influencers, but there are also lots of potential toxic masculinity influences. Society produces and makes use of the kinds of masculinities that they espouse. The kinds of common sense arguments they make about the roles of men and women and heterosexuality are also made by, conservative politicians, hegemonic sex education, (some) TV and film. We are often implicated in supporting this as individuals and collectives. Our lives are organised around outdated modes of work. This (for example) rewards labour coded as masculine (hard, tough, logical) more than labour coded as feminine (soft, caring, feelings). More on this later when we get to how this plays out in schools.

Outsourcing responsibility

It lets us off the hook as a society from tackling this topic by externalising this as a ‘bad outside effect’ we want to get rid of. {I’m all in favour of never hearing from these men ever again. Mostly I hear from them via people that want to critique them.] Outsourcing responsibility to these Others means we obscure the real problems. It also means that we are obscuring the best solutions.

Quite frankly, if these men, these men*, are such a huge threat to this generation of men, what does that say about us? I can understand why teachers are alarmed about this, I’m always in solidarity with teachers. But these basic ‘common sense’ ideas of effect and influence are not helpful. Instead maybe we should accept our own failings, or omissions, as educators.

Our job is to be part of the entanglements of young men. To be resourcing them with tools, technologies, influences, modes of being, the possibilities for joy, embodiment, care, learning. This is what education is supposed to do. So the call from educators should be more ‘we need resources and training and support to do our jobs’ and less ‘what are the authorities going to do about violent misogyny online’ (though that would also be beneficial clearly).

*Neil Kinnock voice

It’s saying men have no agency

It is going to be counter-productive to any work of liberation around young masculinities to say that young men are so easily influenced by these men. It’s basically saying they have no agency (or that they aren’t desiring machines*). The work is to convince young men of the benefits of feminism for them. It’s not that hard: honestly. The same forces which violently oppress the Other are those which violently coerce young men into masculinity. Again, what’s your school doing about this? I’ve written here about how to do RSE with young men.

*I am employing the ideas of agential realism after all.

It others young people

Young people are no more subject to influence than adults. To suggest they are is disempowering and infantilising. We run the risk of reifying the problem that is [current toxic masculinity influencer] by talking up his influence (and the common sense idea that his influence is causing uncritically bad effects in young men). When we should be paying attention to what it might be doing and what else we could be doing as a society.

Researchers consistently find that when we talk about someone being an influence, people will pass on their influences to others. This ‘third person effect’ means that people will think that they won’t be influenced by the influence but other people will. Particularly young people, or people with less social capital (which is one of the big problems with the tea and consent video), or people who are read as being less intelligent and critical than them. It’s infuriatingly patronising. So we can accept that we are critical thinkers in an entanglement of different relations, but that others aren’t. Fuck that.

Be aware of the spectacle

I’ve been a relationships and sexuality educator since 1999. I first got into youth work and RSE in order to work with young men around what we called back then ‘macho values’. So I’ve had first hand experience with misogynistic and violent views and behaviour. Sometimes I’ve been on the receiving end. Overall I think I’m encountering a lot less of this. So we also need to be wary of the spectacle of one person’s infamy. Because if [current toxic masculinity influencer] is forgotten, so will the whole subject of what do we need to do about masculinities. What kinds of resources do young people and teachers need? Consider the possibilities for a society not territorialising certain traits / jobs / roles as masculine and then reifying these in a neoliberal context.

The last 25 years have been spent palming off the responsibility for toxic young masculinities onto influences such as: violent films, Grand Theft Auto, drill, gonzo porn, and now influencers. At no point do we hear about how young masculinities are produced in and around our school systems. This is what we should be talking about.

If you’re already an RSE practitioner, you might want to come on my new Advanced RSE Training course.

What produces toxic masculinites being brought up

So the question for how to deal with this in RSE is to consider what might produce toxic masculinity influencers being brought up by young men. When his name, or the views of the manosphere generally, are brought up with me there is another entanglement going on. I wrote about this recently in this article

mobile phones — Andrew Tate — hormones — fragments of sexual knowledge — trans/queerness — football shirts — nail varnish — chairs — my absence-presence — commitments to marriage — spacious classroom — covid — presence-absence of teaching staff — school rules signs — play-dough — previous sexual experiences — unique cultures — concerns about pregnancy — music — the resources

Added to this in my conversations with young men specifically bringing him or ideas from the manosphere up the assemblage of factors producing this might be:

checking my credentials — my age — the extent of my commitments to feminism and anti-oppression — that they don’t know me — will I (over)react — how interested I am in what they have to say — opening up a conversation — ‘expert’ facilitator — ‘naughty boys’ — queerness — bonding with mates — things they can’t ask but want to — testing my ability to listen — tea and consent video (or other dreadful ‘consent campaigns’)

It’s important to go a lot further than just thinking about the effect that influencers have on individuals. Thinking of what might produce the effect in class (or wherever else) can give us really important clues as to how we might deal with it. It also provides us with some room to think about the kinds of technologies of care we might use to educate and protect them, others, and ourselves.

Motivations and solutions

When we see toxic masculinity being brought up, it’s very easy to just assume that the only motivations for this are because they want to cause harm. This might be true of course. And if someone is doing harm, it needs to be dealt with like any other harm, either via safeguarding protocols or bullying policies, or how you deal with violence in schools or colleges.

However, it is worth thinking about some of the motivations for why someone might be doing toxic masculinities. This also gives us some space to think about how we might un/produce them, to think about solutions, and to provide lines of flight for their masculinities to become other.

Discomfort and disconnection

Perhaps in the process of saying something out loud they want to see how long these ideas can survive in the offline world, with people, relations, reputations, and the risk of disconnection. The manosphere have spaces for men to produce and reproduce an armour which seeks to contain the fragile and disconnected masculinities of its participants. Maybe they want to test this in the ‘real’ world.

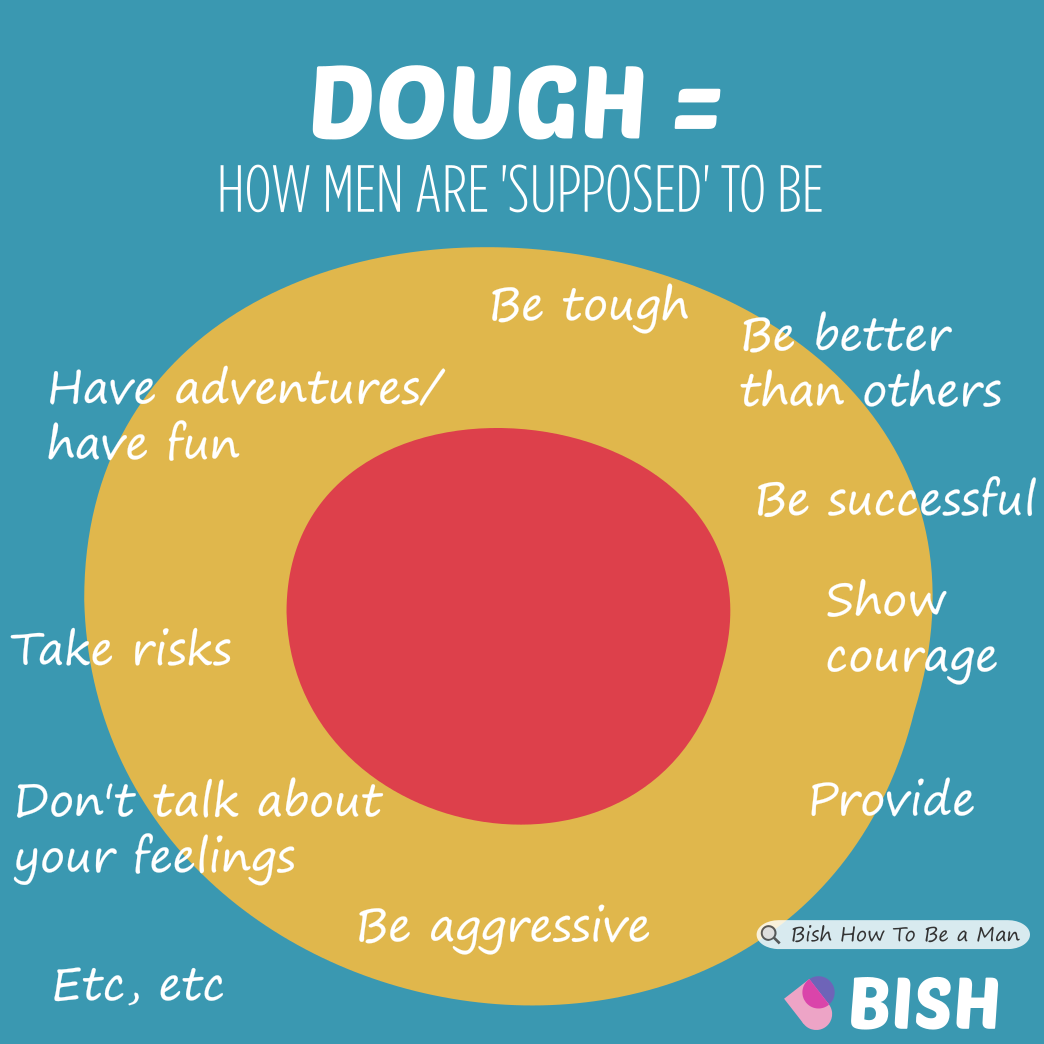

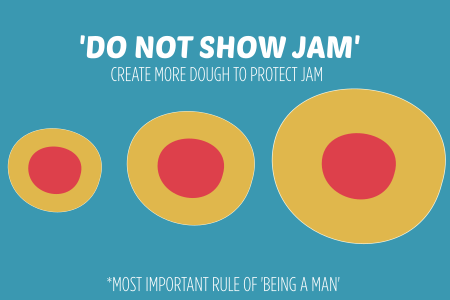

They might also be revealing a sense of their own discomfort with their unconscious, or what makes them vulnerable. I talk about how hegemonic masculinity forms the dough of a jam doughnut. When the jam (feelings) are at risk of being revealed they create more hegemonic masculinities to cover it up. Consider the young man who isn’t popular, isn’t sporty or athletic, isn’t wealthy, isn’t considered attractive, what kinds of masculinities are left available for them to produce? Violent, misogynist, and oppressive ones.

RSE and Recognition

It might be in response to the curriculum. They are saying ‘I want to talk about gender, particularly my gender.’ How does your curriculum or school present masculinities? Do you have a great deal of RSE? If you only have a bit, how else does your school produce young masculinities? If your curriculum is simply producing a discourse of young masculinities as being perennially the problem, then you’re part of the problem. See also if your RSE uncritically produces a heteropessimism. Again, I’ve got plenty more on this here.

They might be seeking recognition. As Jacob Johanssen writes in Fantasy, Online Misogyny and the Manosphere: “It needs to be stressed that the very creation of their toxic identities undermines recognition by the other. However, this does not mean that they would not deeply desire a sense of recognition which goes beyond the immediate one of their male communities.”

You might be thinking, I wish I could get men in my school / community who would be up for doing this work. IKR? That would be very helpful. However a) hegemonic masculinities disallows this in men even if they are teachers, and b) women can be very good at doing this work too. (Shout out here to the brilliant women who trained me to do this work.) What we need is a structural change where the status of RSE is boosted. For example: there’s more time in the timetable for RSE, there’s more money for training and resources, the PSHE co-ordinator being on the same pay as head of department or year. Make a bigger pie and then see how we slice it up.

Can we show a different way?

Perhaps they might be testing us and our response. What if the hateful things they were saying about the other (women, queer folk, anyone who is a ‘phallic’ threat to a fragile masculinity) mirrored, or in some way replicated, the hatred they might feel for themselves. Jacob Johanssen talks about this as ‘dis/inhibition’ (I’ve massively oversimplified it though).

Maybe also they want you to experience some of the fear and sadness that permeates their gendered identity (which the manosphere thrives on). Perhaps they are just asking for the smallest glimmer that you can offer them a different kind of masculinity to hold on to? What are the possibilities for our responses to create a new line of flight where they might become a different kind of masculinity.

As Laura U Marks says in her chapter in Spectres of Fascism (I got this from Jacob’s book) “There are lots of cultures and subcultures of men who don’t cultivate or reject the armoured ideal [of the Freikorps soldiers, or alpha masculinity]. In North American societies, there are slackers, dropouts, ‘sensitive men’ (sometimes). Bears and puppies who push back against the gay hard body-cult. Born males who reject the gender and try out a third path. ‘Lesbian boys’. Stylish men. Men who grow old gracefully. Men at ease with their sexuality. Gentle fathers. Gamers who manage to balance the imaginary body adventuring in virtual space and the soft, flabby, physical body at the console. There are so many kinds of lovely men.”

Small interventions can make a huge difference

Certainly over my career (having worked with thousands of young men in person and millions online) I’ve had the most successful interventions with young men when I can pause, breathe, and ask questions that might help them do this. “What does that do for you?” “What else?” “What difference would it make to you if …?” “I’m noticing that you’re het up, is everything okay?”

I do this with young men who don’t know me at all (which has its advantages and disadvantages). If I don’t co-produce this toxicity, (locking horns, giving them a bollocking, backing them into a corner) but gently challenge them and open up a space for them to be better, the outcomes can be staggering. Young men are so desperate for nourishment and care. They will ask for it even if you show the slightest signs that you are willing to offer it.

It’s not easy to do this, but be encouraged by the idea that all these young men want from you is a glimmer of hope that they can become other. How can you respond to someone that will show them that different kinds of masculinities are possible?

Keep paying attention to what’s better

We might need to be creative in how we tackle it. Making sure we make and stick to group agreements. Only having discussions with young men in their small groups. Quiet words after class. Keeping a pastoral eye out in the rest of the school. But if you can, what might be the smallest sign that a young man has become non-toxic? What might you notice? Is there anything he might notice in your response? This kind of ‘what’s better’ way of thinking is from solution focused therapy and is a way of seeing the resources not deficits.

Showing this kind of compassion for young men doing toxic masculinities is not going to land well with everyone. But if we see it as a form of safeguarding and harm minimisation for everyone else, as well as the young men themselves, then we might start to see things from a different perspective. It’s not like everything else has been working.

(A few more) Tips on how to deal with toxic masculinities in RSE

The discourses about all of this can really zap our confidence and it makes it all sounds very scary. Doing this work is a bit easier than it sounds and I would be doing a bad job if I were to say that it was too hard for you to do. Here are a few more things that I’ve found very helpful, but it might be a better idea for you to reflect on what has worked for you and to talk about this with colleagues.

Safety via group agreements

The first thing to do is to keep the class safe. If young men are choosing to repeat harmful discourses, we need to make sure that we reduce the possibility of this harming others in the room. This can, of course, include us. This is why having a group agreement is really important. Group agreements means that any discussion we have has to be had in good faith, where we really try to use language that is appropriate, and is not harmful. It’s about recognising that relationships, sexuality, gender, the self, are really tricky topics and we need a lot of care to make sure it will go okay.

It’s also really important when we create a group agreement, which may be about vibe or scene setting, that we make explicit that this kindness and care to everyone in the room, including young men. If, when we frame a group agreement, or introduce a class, we fix young men in the social location of ‘likely abuser’ then this is going to form part of an assemblage which might produce someone bringing up someone from the manosphere.

Just do small group work

Small groups really helps with this. I very rarely work with a whole class at once. It’s much better to put people in small friendship groups and give them a really interesting and challenging activity to do, rather than just work in one big group. This way we can reduce risks but also have opportunities to have interesting micro-facilitations responding to the specific needs of the groups.

So I could be answering questions about pregnancy risks, be asked for nail polish tips, having a conversation about transitioning, and be asked provocative questions like ‘how many genders are there’ all in the same class whilst keeping the risks of harm low, taking part in each discussion as I find them, and everyone having an interesting lesson. I very rarely ask the whole class to take part in the same discussion with me standing at the front of the class.

Pay attention to what you’re bringing

RSE or any education for that matter doesn’t happen outside of you. I think it’s useful to think about you as being part of an intra-active flow of education rather than an ‘expert’ teacher interacting with ‘inexpert’ students. I really like this definition of this.

“Intra-action is a Baradian term used to replace ‘interaction,’ which necessitates pre-established bodies that then participate in action with each other. Intra-action understands agency as not an inherent property of an individual or human to be exercised, but as a dynamism of forces (Barad, 2007, p. 141) in which all designated ‘things’ are constantly exchanging and diffracting, influencing and working inseparably. Intra-action also acknowledges the impossibility of an absolute separation or classically understood objectivity, in which an apparatus (a technology or medium used to measure a property) or a person using an apparatus are not considered to be part of the process that allows for specifically located ‘outcomes’ or measurement.”

This means how you respond, what mood you’re in, and what you’re seeing (or what you think you’re seeing) is as much a part of the lesson as your students. Honestly, the best lessons I facilitate are those when I am really believing in this. It means that I can stay calm, curious, and kind. This helps the students to do the same and the outcomes can be amazing.

Don’t debate

Debates in class are just the worst. I also always have to remind myself not to lock horns with people either. A few stock responses I always have are:

“I don’t know, what do you think?”

“Some people think that, but other people think different things”

“Oh that’s interesting, what makes you think that?”

“How is that useful idea for you?”

“Of course not everyone is going to agree with that, but you do you.”

“A better word for that is ___________ but yeah I understand what you’re saying.”

Trying to intellectually defeat people’s arguments makes for incredibly dull RSE and has some possible backfire effects. If we spend a lesson arguing with someone who is a fan of men are essentially this and women are essentially this, then we’ve taken up a huge amount of space. We’ve given our interlocutor space and time for their arguments, which reifies the arguments. This can have a backfire effect of making their arguments seem like they have something to them. It also prevents us from looking at a subject from lots of different perspectives.

Preventative work

Clearly the best thing to do is preventative work. Reactive RSE is usually a sign that you’ve not been doing a good enough job in your school for some time. It’s also likely to be crap. Ticking a box in order to say that you’ve covered a topic where really it’s just providing cover. Young people can see right through it. I know this because often they tell me this when I come into schools. There are tons of activities in my resources that you can use with all students to explore gender and sexuality.

Support my work on this

If you join the BISH Patreon at the £10 a month tier you’ll find this article, with a resource you can use in class, and loads of other self-reflexive resources. BISH is my website for young people, which is very popular with young men. Thousands of young people are getting their sex ed from BISH. It’s an important corrective to right wing discourses about sex and relationships, particularly those from the manosphere.

For example, late last October / early November, we (I) had an influx of thousands of young men wanting advice on how to survive No Nut November. Find out more about this by becoming a Patron today. £10 a month on the Educator Tier gets you access to additional resources, but £1 a month will help me keep it going. I just need 2000 £1 a month subscribers and I’ll stop asking. 4000 and it’s a full time job. That’s at patreon.com/bishuk

© Justin Hancock, 2023

Justin Hancock has been a trained sex and relationships educator since 1999. In that time he’s taught and given advice about sex and relationships with thousands of young people and adults in person and millions online at his website for young people BISH. He’s a member of the World Association for Sexual Health. Find out more about Justin here and stay up to day by signing up for the newsletter.